THE 10 PRINCIPLES OF DISABILITY RIGHTS

People with disabilities all over the world have endured unequal treatment and discrimination on the basis of having a disability. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has drawn international attention to how the situation can be acknowledged and redressed through a country’s laws. These principles capture and illustrate common elements of effective disability rights laws around the world.

-

1. People with Disabilities are Experts

-

2. Full Participation

-

3. Cross-Disability Coalitions

-

4. Champions for your Cause

-

5. Defining Disability

-

6. Reasonable Accommodations

-

7. Checks and Balances

-

8. Specific Regulations

-

9. No Rights without Remedies

-

10. Common Cause Across Social Movments

People with Disabilities are Experts

A disabled woman activist from Jordan

-

Philosophy

-

Example

People with disabilities and their allies must be extremely knowledgeable about the law. A common problem in many countries is that people with disabilities themselves are not aware of the rights they have, and do not know how to file a complaint or to let the authorities know when their own laws are not being enforced.

When discrimination occurs, there is often no one else present except the person or entity that discriminates and the individual being discriminated against. Disability discrimination cannot be successfully exposed and rooted-out without the active knowledge and participation of people with disabilities.

A society must have large numbers of people with disabilities and their allies who understand and take responsibility for their own laws, and are ready to use whatever means they have to let authorities know when disability rights laws are not being implemented. The cross-disability community must continue acting until the laws are finally being enforced.

Some disability rights laws hold a hospital responsible for providing sign language interpreters to deaf patients. In order to ensure that the law is enforced, a person who is deaf and using hospital services (and their family) needs to know that the law exists, what the law says, and what are the options if the hospital fails to honor their rights. For example:

- Can they safely report the hospital’s failure through a letter or a call to an ombudsman, file a complaint with a designated enforcement agency, or find a rights attorney who will file a case on their behalf in the courts?

- Are there any resources that will help them with the costs of taking these actions?

- Are there disability advocates or organizations that will help them write letters or complaints?

- What kind of information will they need to provide to help with an investigation of the complaint?

- What consequences might they face if the complaint is unsuccessful?

Similarly, if a law allows some students with disabilities to have extra time for test-taking, a student with a learning disability must know about that law in order to access their right to reasonable accommodations. If a person with an intellectual disability is denied the right to vote despite her capacity to understand what voting means and make a personal choice, she needs to know that she has a right to vote under the law and how to do something about the denial of that right.

People with Disabilities are Experts

A disabled woman activist from Jordan

People with disabilities and their allies must be extremely knowledgeable about the law. A common problem in many countries is that people with disabilities themselves are not aware of the rights they have, and do not know how to file a complaint or to let the authorities know when their own laws are not being enforced.

When discrimination occurs, there is often no one else present except the person or entity that discriminates and the individual being discriminated against. Disability discrimination cannot be successfully exposed and rooted-out without the active knowledge and participation of people with disabilities.

A society must have large numbers of people with disabilities and their allies who understand and take responsibility for their own laws, and are ready to use whatever means they have to let authorities know when disability rights laws are not being implemented. The cross-disability community must continue acting until the laws are finally being enforced.

Some disability rights laws hold a hospital responsible for providing sign language interpreters to deaf patients. In order to ensure that the law is enforced, a person who is deaf and using hospital services (and their family) needs to know that the law exists, what the law says, and what are the options if the hospital fails to honor their rights. For example:

- Can they safely report the hospital’s failure through a letter or a call to an ombudsman, file a complaint with a designated enforcement agency, or find a rights attorney who will file a case on their behalf in the courts?

- Are there any resources that will help them with the costs of taking these actions?

- Are there disability advocates or organizations that will help them write letters or complaints?

- What kind of information will they need to provide to help with an investigation of the complaint?

- What consequences might they face if the complaint is unsuccessful?

Similarly, if a law allows some students with disabilities to have extra time for test-taking, a student with a learning disability must know about that law in order to access their right to reasonable accommodations. If a person with an intellectual disability is denied the right to vote despite her capacity to understand what voting means and make a personal choice, she needs to know that she has a right to vote under the law and how to do something about the denial of that right.

Full Participation

A conference in Mexico includes audience members with and without disabilities

People with disabilities must have access to all aspects of political, civil, economic, social, and cultural life. There are many circumstances where people with disabilities encounter discrimination. Disability rights laws should address all of these circumstances, from obtaining healthcare to seeing a movie, from employment to housing, from the issuance of a driver’s license to airplane travel, because people with disabilities have the right to equal participation in every aspect of society.

This does not mean that there must be a single law that addresses every possible circumstance in which disabled citizens can encounter discrimination. People with disabilities in a particular country may decide to choose on a particular subject area or proposed law that would best serve as a strategic focus for the attention of lawmakers and the public. For example, a cross-disability community could choose to lobby first for accessibility in government buildings, or employment of people with disabilities, or accessible transportation. In addition, some countries may have existing laws, some of which address a particular issue like voting or people with particular kinds of disabilities, that are not disability rights laws but continue to serve a needed purpose.

In the U.S., some of the earliest national disability rights laws banned discrimination in government funded services and in public education. Specific states also had building laws that included disability accessibility requirements. The passage and implementation of these older laws contributed to the eventual development and passage of the far broader Americans with Disabilities Act, which deals with disability discrimination in both government and private businesses, in the areas of employment, transportation, physical accessibility, and telecommunications.

Cross-Disability Coalitions

A group of women with different disabilities meet to address common barriers and challenges

People with disabilities and their families all over the world have historically fought for rights that apply to their own specific disability (i.e. people who are blind fought for the right to receive an education and the use of Braille materials, people in wheelchairs fought for ramp entrances into buildings, and so forth). But people with many different kinds of disabilities and chronic conditions all face common barriers of discrimination, prejudice, and stereotype. If they, their families and friends, and their advocates combine the influence they have as consumers, voters, individuals, and as groups who communicate through the press and social media, the disability community overall will gain a cohesive identity and force that is not obtainable any other way.

People with disabilities need to be disciplined, open-minded, and strategic to achieve the promise of this principle. Specific disability groups may recognize stereotypes that are directed at them, yet still hold prejudices and stereotypes about people with other disabilities. Some groups may have had past conflicts, and there may be communication challenges, but ultimately coalition leaders must hold together all kinds of disability groups including:

- People with apparent and non-apparent disabilities

- Parents of children with disabilities

- Disabled people’s organizations

- Organizations that offer services to people with disabilities

When things become difficult, emphasize the goals you hold in common:eliminating discrimination, abolishing all disability barriers, sustaining reasonable accommodations, and building equal opportunities. Never sacrifice one group for a short-term victory, even if it’s an important one like the passage of a hard-fought law, because it will always make the coalition weaker over the long-term.

Working across disability groups also establishes a base of people who are knowledgeable about the law and recognize that rights will be achieved only when people with all types of disabilities experience equality. This cross-disability base can mobilize and respond when laws are scrutinized or revised, to uphold shared principles and continue to serve as a unified group for their rights.

A truly inclusive law will lend credibility to coalition leaders as they emphasize cross-disability inclusion as a central theme when talking to politicians, the media, and people with disabilities themselves. This core principle must also guide practical decisions; coalition leaders demonstrate their commitment to inclusion by ensuring that trainings are held in wheelchair accessible venues, sign language interpretation and alternative formats materials provided, and other accommodations made to ensure access to the full range of people in the disability community.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was written to protect people with many different types of disabilities, including cancer, mental health disabilities, HIV/AIDS, history of substance abuse, multiple chronic conditions, and functional limitations.

Just before the ADA was passed into law, restaurant trade associations realized that the law would protect people who have HIV/AIDS from employment discrimination. If the law passed, it would be illegal to refuse to hire, or to fire, against qualified waiters, dishwashers, and cooks, just because the employer knew or suspected that they had HIV/AIDS. Restaurant associations threatened to campaign hard and get politicians on their side unless people with HIV/AIDS were explicitly excluded from the ADA. Instead of bowing to great political and public pressure, the disability leaders and organizations that had come together around the law refused to turn their backs on the HIV/AIDS community, people and groups that had been key allies in the long fight to pass the ADA. They knew what science had already discovered about HIV/AIDS and understood that the condition is not casually contagious. A person with HIV/AIDS, particularly in the early stages of the condition, can safely work around food without putting others at undue risk. If the cross-disability coalition allowed the law to exclude persons with HIV/AIDS, the coalition would basically be participating in the very stereotypes and prejudices that the law was supposed to be fighting. The coalition stood firm, and the law passed.

Champions for your Cause

The Mayor of Gymuri, Armenia meets with disability advocates in 2014

Whether a country is democratic or socialist, has a monarch, or is a federal republic, as long as there is some acknowledgement of the rule of law and a system of government representatives who create and administer those laws, it is important to have allies among those government representatives who understand disability rights.

Disability can be experienced in many ways and it transcends any political party, race, gender, and economic class. An individual can be born with a disability, acquire one through an accident or chronic condition, have a child or family member with a disability, age into a disability, or marry someone who is connected to disability in this way. Finding influential leaders who have experienced disability to be your champion is key. These are individuals who:

- Will have experience with, or at least be open to learning about, the multiple kinds of discrimination and barriers experienced by people with disabilities.

- Will be able to personally express the goals of disability rights laws and the reasons that laws are needed when they speak to their colleagues, and will be able to connect other disability rights leaders with important political and social forums.

- Will have trained legal staff that can assist with the actual development of bill language, and alert a disability coalition about opportunities and risks as a proposed bill advances toward becoming a law.

- If the government representative has disabilities him or herself, they also help fight a major stereotype that people with disabilities have limited capabilities and future prospects.

Politicians from both of the United States’ major political parties who fought to bring the Americans with Disabilities Act into law included a person with diabetes, a veteran who lost his arm fighting in a war, and a person with a deaf brother. A key staff person in the U.S. White House, who had watched her mother discriminated against by insurance companies because of a bout with cancer, was instrumental in ensuring that the 2008 Affordable Care Act of President Obama required private insurance companies to sell healthcare insurance to people with pre-existing conditions (historically healthcare in the U.S. excludes pre-existing conditions).

Defining Disability

A young woman with a disability enjoys adaptive biking

Disability discrimination laws start with the understanding that people with disabilities are full human beings with the same potentials, capacities and worth as other human beings. They can recognize that people with disabilities need benefits because of inequality, but also recognize that the root of inequality lies in a long history of unequal economic, social and political opportunities for people with disabilities (not just the natural consequence of an individual’s medical diagnosis). Disability discrimination laws acknowledge the many factors, such as prejudice, stereotypes, misplaced pity and physical barriers that together have the consequence of stopping people with disabilities from achieving their highest potential. These laws should:

- Explicitly acknowledge the existence of discrimination against people with disabilities

- Recognize the disabling impact of longstanding physical, social, economic, political, and cultural barriers

- Should not define disability purely in terms of a medical diagnosis

Different from disability discrimination laws are benefit laws, which almost always define disability using medical criteria, and focus on what people with disabilities cannot do. Many countries, including the U.S., have laws or policies that provide benefits, such as income support, low-cost healthcare, or other forms of assistance to people with disabilities and their families. These laws serve an important purpose and are needed by people with disabilities who do not have equal opportunities in such areas as employment, education, housing, and transportation.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has a three-pronged definition of disability. The third prong, and to some extent the second, acknowledge how society itself can disable a person by treating them as if they have a physical or mental impairment, and therefore forcing them to deal with many barriers to their full participation in society.

- First prong: The most medically oriented, stating that disability is “the presence of a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.”

- Second prong: States that disability includes having a history or a record of such a physical or mental impairment.

- Third prong: Recognizes that someone has a disability if he or she “is perceived by others as having such an impairment.”

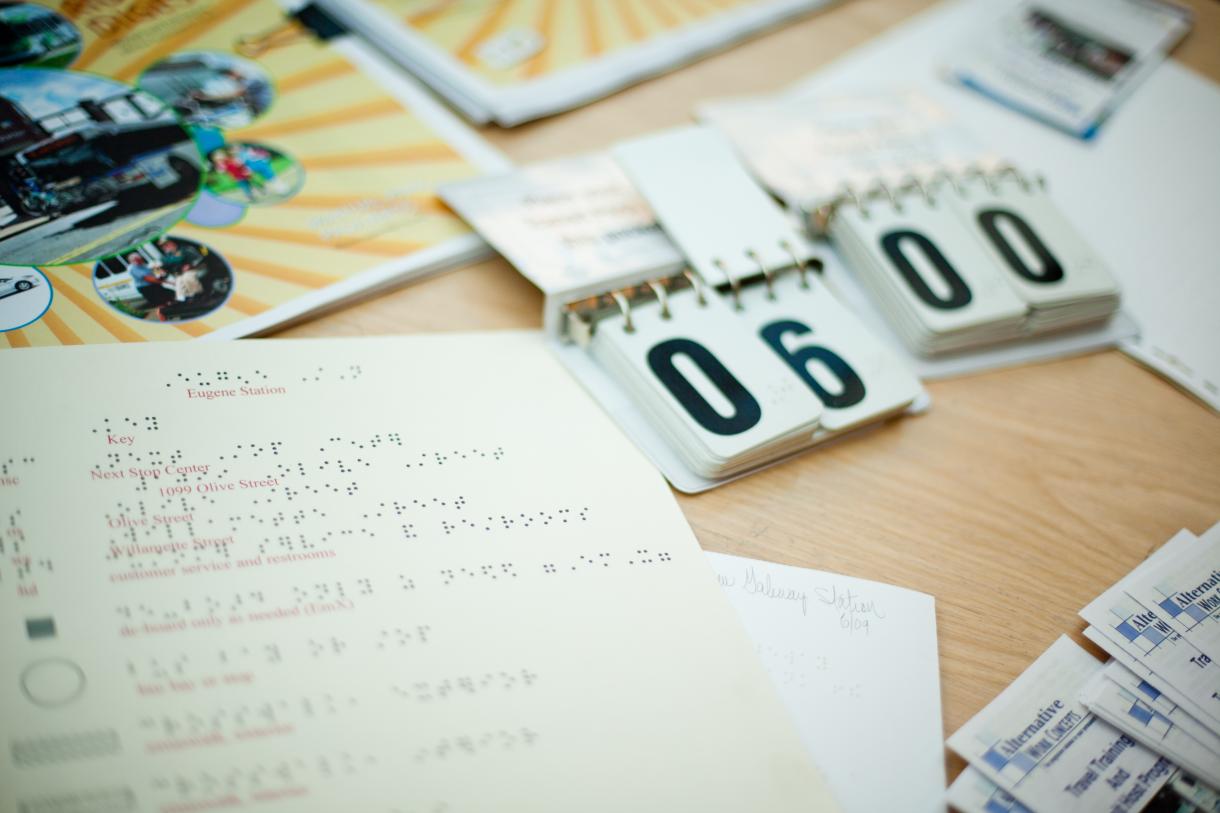

Reasonable Accommodations

Alternative formats such as braille and large print are examples of reasonable and low cost accommodations.

People with disabilities do not have an equal right to participate if they are individually left to overcome physical barriers and historical ways of doing things that exclude them. The wheelchair user’s right to enter a building or use a bus that only has stairs is an empty right. The right of a person who is deaf to attend a good university is meaningless if she is not given access to the content of the classes through a sign language interpreter.

As a result, disability rights laws cannot solely grant people with disabilities the right to be treated exactly the same as everyone else. The term “reasonable accommodation” was coined to designate the various kinds of modifications that may need to be made so that people with disabilities have the same opportunities as people without disabilities to live full lives in their communities.

While reasonable accommodations can require an initial investment, in most cases the amount is relatively small. When you think of strengthening communities and improving the lives of community members, the investment to provide reasonable accommodations is economically advantageous because it will allow the population of people with disabilities to be active members of society by obtaining an education, contributing to the workforce, and become contributing members of society as a whole.

Examples of reasonable accommodations include:

- Raising a workplace desk so it is accessible for a wheelchair user

- Providing assistive technology or alternative formats for people with visual disabilities

- Ensuring extra time or quiet spaces for people with learning, psychiatric or attention disabilities

- Having a flexible work schedule for someone with a chronic health condition who needs more breaks or has a medication schedule that makes it difficult to rise early

- Providing a scribe to take notes for someone with a visual or intellectual disability

- Providing a sign language interpreter and captions for people with hearing disabilities

Checks and Balances

Replacing old buses with accessible buses will avoid a single great expense and the local bus system will become increasingly accessible over time

A strong and sustainable law should contain checks and balances to show that disability-related accommodations and modifications are reasonable and not unlimited. A proposed law will more quickly pass, achieve public support, and be effectively implemented if it is perceived to be a fair law, not only for the minority group whose rights are recognized, but for all parts of society. People with disabilities have a right to reasonable accommodations (RA) and barrier removal, but those rights can be balanced in a number of ways.

This is important because if the law itself establishes possible limits on RA, it helps to silence critics of the law who may try to raise fears about how the law is too expensive, puts people out of business, and gives people with disabilities too many advantages. Moreover, if the law is clear about how a limit works, then people with disabilities are likely to be more confident about raising their right to accommodations. Checks and balances allow people with disabilities to participate as contributing community members and break down perceived notions that they are a burden to society.

Scenario: A person using a wheelchair wants to buy clothing at a small family-owned store but there are five steps at the entrance and not enough space to install a ramp. Under the ADA, the business owner would not be required to make the store wheelchair accessible if they can prove that the cost of construction would be beyond their financial means, or an “undue financial burden” on the business. However, the business owner would still be required to provide RA in an alternative way, such as using a bell or intercom system at the street level, so customers maintain their right to service.

There are many factors that can be considered in establishing limits on reasonable accommodation:

- Different limits can be established for different entities depending on the resources of the affected entity. For example, a government agency or large profitable business likely has more financial capacity to make changes for accessibility than a small family-owned business.

- Different limits can be considered depending on the kind of accommodation that is being requested. For example, it may make sense to have some kind of limit on how much a doctor would have to do to make their second floor office in an old building accessible. However, that does not mean the that there should be a similar limit on the doctor’s obligation to take extra time for a patient with a developmental disability or provide Braille information to the blind parents of a child who is a patient.

- Limits can be applied that relate to public safety and ensuring that employees hold jobs that they are qualified to do. For example, the right of a job applicant or employee to seek accommodations can be limited if an employer can prove that the applicant cannot perform the essential functions of a job even with reasonable accommodations, or if the employer can prove that an employee cannot perform a job without presenting a danger to himself or others. The assertion that someone with a disability cannot perform a job or is a safety risk must be based on real facts and not just stereotypes. Someone who is deaf or hard of hearing may be limited in their capacity as a sound engineer because it is not possible for them to experience the full aesthetics of recorded sound, but full hearing is not necessarily required to be a safe truck driver with good routines of mirror and sight-checks.

- Different limits and standards for new structures/purchases versus old buildings and existing systems can act as an overall check and balance on barrier removal. For example, a city or a company might be required to purchase only accessible buses as it replaces its vehicles, but not required to immediately replace its fleet with accessible vehicles. This means that the city or company will not have to undertake a single great expensive change, but the bus system or fleet will become increasingly accessible over time.

Specific Regulations

Clear regulations are important so citizens can understand and comply with the law

At this point, many countries around the world have laws on the books that ban discrimination or protect the rights of people with disabilities. However, very few countries have laws that are being implemented, and one of the common reasons is the absence of practical and enforceable implementation details.

The law can use grand language to declare that people with disabilities will no longer be discriminated against and will be provided equal rights, but there must be tools for implementation such as federal, state or local regulations, enforceable standards, and forums to address disputes that show practically how to get from a barrier-filled world to the ideal of the law.

Additionally, specific timelines need to be set, for example, when modifications need to be completed or when new buildings need to become accessible.

Having very specific regulations and timelines on everything from the width of a doorway, to web accessibility, sidewalks and other infrastructure, makes compliance with the law very measurable.

When the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed, it contained very specific timelines for implementation. For example, every new bus had to have a lift for a wheelchair; therefore, considering the turnover rate to new buses, all buses would be wheelchair accessible within 20 years. There are also very specific regulations, guidelines and timelines on modification of old and construction of new structures.

Regulations need to provide answers to questions such as:

- What are the requirements of an “accessible” building? What does an accessible building look like? How wide are the doors and how high are the counters and sinks? How steep can the ramp be? Where should Braille signs be placed on walls and in elevators?

- On what timeline do buses have to be equipped with a lift or the capacity to “kneel”?

- When in route, how often should transit operators call out the street locations of stops?

- What are the requirements to make communication “accessible” for someone who is deaf or hard of hearing? Who is responsible to pay for a sign language interpreter, and under what conditions?

- How must schools determine the needs of students with disabilities, and when are they required to provide reasonable accommodations and policy modifications for the child’s education?

- If a person with a disability has a dispute with a government entity, a business, or an employer about reasonable accommodations, how can that dispute be resolved? What is the timeline for disputes to be filed and resolved?

- What agency or group is responsible to find answers to the questions above? Who is responsible to establish standards that become legally binding? What is the required process? How are standards changed as society changes and new technologies are discovered and applied?

These are just a tiny sample of the questions that need to be asked and answered once a law is passed.

As a strategic matter, the cross-disability community might decide to prioritize the areas that it wants regulated first. Once significant implementation details are set for a particular focus area, such as physical accessibility or transit or education, then the community can tackle another topical area.

As every person with a disability knows, details matter. If the details on implementation of the law are just left up to individual businesses, government employees, schools, and employers to determine, without additional enforceable guidance, they are likely to get it wrong.

No Rights without Remedies

A requirement that employers meet quotas is a good example of how remedies support sustainable change.

Just like any other law, disability rights laws will not be effective without consequences that are enforced when the law is broken. A true remedy has two parts:

- There must be a way for the enforcement agency to monitor whether people are actually complying with the law. Common ways of monitoring for compliance include: requiring entities covered by the law to file reports; soliciting and investigating complaints from people with disabilities and from the public on breaches of the law; and sending out agency representatives — openly or “under cover” — to check on compliance firsthand.

- Once a violation of the law is found, the agency must have the recognized authority to enforce the law’s consequence. Common consequences include: paying a fine; paying monetary damages (compensation for harm done) to a person with a disability; forcing an entity to remove the existing barrier and/or to comply with the law in the future; or some combination of these.

The consequences of breaking the law have to be significant enough to incentivize compliance with the law by covered entities, whether they are individuals or large companies. The price of breaking the law cannot be so easy that entities will be willing to pay repeatedly while ignoring the law. In other words, the law has to have “teeth”: it has to have a “bite” if you don’t obey it. In addition to financial consequences for non-compliance, the responsible entity should also have to remedy the situation. This provides not only incentive, but a mechanism for enforcing the changes that will enable people with disabilities to participate in every level of society.

If a large company discriminates against a person with a disability, the fine that they have to pay must be significant enough to motivate them to change their behavior positively in order to avoid future fines, rather than just find better ways to not get caught.

A number of countries have laws that require government agencies and private businesses to meet employment quotas for certain minority groups, including people with disabilities. The purpose of requiring that a certain number of percentage of employees be people with disabilities would be to increase employment opportunities of people with disabilities, and would also have the effect of dispelling stereotypes by increasing interaction among people with and without disabilities.

The employment quota will only be effective if:

- There is a significant consequence, such as a fine, for failing to meet the quota.

- There is a mechanism defined for a person with a disability to make an official complaint to an enforcement agency or to judicial courts about an employer’s failure to meet the quota.

- There is active investigation of complaints or non-compliance with the law.

- There is a mechanism to actually collect an imposed fine and/or ensure that the employer will change practices to meet the requirements.

- Employers cannot easily circumvent the purpose of the law, for example by hiring employees with minor impairments such as farsightedness and classifying them as employees with disabilities, or by hiring people with disabilities for lower pay than other employees or restricting their opportunities for advancement.

Common Cause Across Social Movements

WILD participants from around the world gather to march in the Women’s Day parade.

Historically, successful and sustainable human rights movements are those in which significant segments of society recognize the need for change. Those who are most directly harmed by particular laws, government policies, and social/cultural practices come together to form a leading advocacy movement but then also implement outreach, education, and alliances with other sympathetic social movements. In the U.S., this strategy was used successfully by the Civil Rights Movement, led by African American people, and continues to be used by the Disability Rights Movement.

When aiming for improved legal protection, it is important for disability activists to reach out to leaders from other pre-existing social movements who can share expertise and advice on strategies for effective laws, regulations, and policy. Experts from other rights movements may also be able to identify existing anti-discrimination or human rights laws that can be used as leverage or models for combating discrimination against people with disabilities, even if disability-discrimination is not explicitly mentioned.

Leaders from allied movements may offer valuable practical support for disability movement actions–for example, by sharing lessons learned, making introductions, offering in-kind or material contributions, or mobilizing their constituents to show support for disability rights causes and activities. Allies from other movements with access to policy-makers may begin to raise disability rights issues and include disability rights leaders and advocates at influential meetings, as well as serve as a conduit of information regarding developments that may impact disability laws and policies.

It is equally important for disability rights proponents to recognize and support other movements, such as those advocating for the rights of women, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ or indigenous persons. Investing in relationships with other movements recognizes the reality that many different personal characteristics co-exist within individuals, expands the network of disability rights allies, and encourages other movement leaders to incorporate a disability lens in their own work. Some leaders in the US disability rights movement were women, gay or lesbian, or members of a particular racial or ethnic group. These leaders remembered and deepened their existing relationships with other non-disability movement leaders and did not forget the needs of these other movements, even as they advanced the disability movement agenda. This takes extra time and commitment, but a disability rights movement must be inclusive to be truly sustainable over many decades and also must help ensure that disability reaches into every policy area that has an impact on people with disabilities.

For example, disabled women activists need to engage with mainstream women’s rights organizations to ensure that the fight against gender-based discrimination includes the voices and concerns of women with disabilities. Laws and policies designed to protect the rights of women in areas such as access to health care, employment, and ending violence should, by definition, include protection for women with disabilities.

In the United States, a diverse array of social movements became involved in the struggle to pass regulations to enforce Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. In April 1977, disability rights leaders and coalitions undertook what became a 26-day takeover of a federal building in San Francisco, California, to pressure the Carter administration into signing and implementing Section 504 regulations. Non-disability advocacy groups provided needed support outside the building because anyone who left the building would not be allowed to return. For example, the Black Panthers (a movement of African American activist) and the Gray Panthers (activists fighting age discrimination) donated food, supplies, and funds for such needs as medications and medical equipment to support the protesters inside the building.

Even after the struggle for 504 regulations, disability activists continued to be an integral part of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Members of the disability community worked with leaders of the civil rights conference on various issues that were important to all civil rights movements, such as a 1991 Civil Rights law that helped amend how employment discrimination cases, including disability, could be brought, proven, or compensated in court. The Leadership Conference also provided strategic feedback and political support when the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 was passed to rectify the impact of a series of key disability discrimination cases from the US Supreme Court.